Funding against the odds

How entrepreneurship is stacked against women and BIPOCs in the United States

Entrepreneurism. The great equalizer. Have a great idea, hustle and grind enough and anyone can build a successful business. There’s just one problem – this couldn’t be further from the truth. The fallacy of meritocracy that is so often conflated with entrepreneurship lacks the contextual awareness that businesses are built within a system – one that often stacks the odds against women and black, indigenous and people of color (BIPOCs).

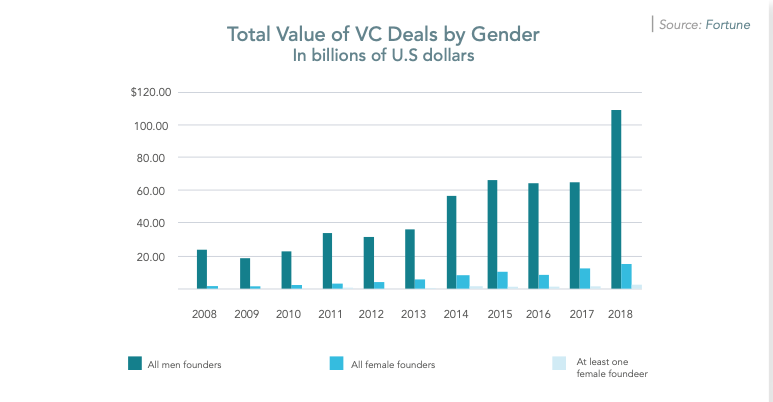

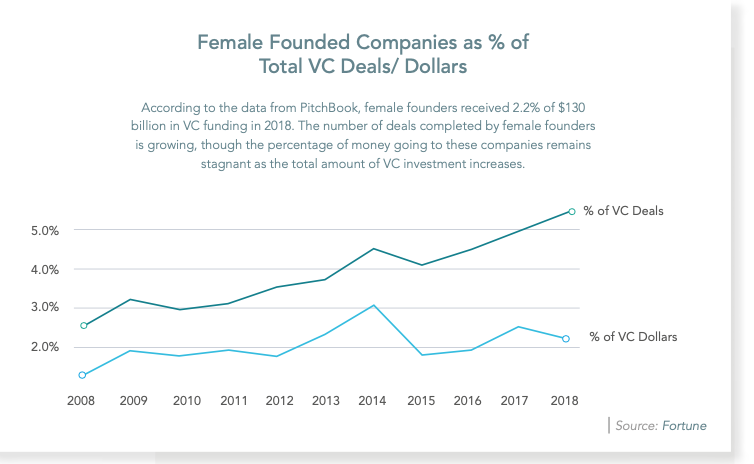

Startup capital is the lifeblood of entrepreneurship, but the barriers to that capital run deep and wide. Don’t believe it? Let’s look at some facts: in the US in 2018, men received 98% of venture capital funding. Ninety–Eight–Percent. Let that sink in. Women-led startups are less likely to successfully raise funding as compared to men, and the odds for women of color are even lower. In a study by Morgan Stanley, companies led by women of color represent less than 1% of total VC funding, with black women raising around 0.0006% of the total $424.7 billion in investments made over the last decade. Latinx women fared marginally better with a paltry 0.32%.

These infinitesimally small capital commitments are sadly a manifestation of the larger system of privilege and inequality at play. The Black Lives Matter movement in the US and across the world calling for a global reckoning on how we discuss race, understand its pervasiveness in power structures, and the calls to reform, defund, rectify, reparate and to generally do better gives us a tremendous opportunity to be introspective about our own industries and reflect on how we can do better. To this end, let’s deconstruct the typical entrepreneurial process to raise capital to better understand the invisible obstacles that lay before women and BIPOCs.

The first way to fund your startup in its earliest stages is typically to “bootstrap.†This requires you to personally fund the costs of launching your business. The only problem with this method is that it is primarily a luxury of the economically advantaged. Bootstrapping presupposes that you have a sufficient level of wealth to not only cover your startup’s costs but to also cover your basic costs of living – an achievement that many in the developed world still struggle with, let alone in the developing one.

Bootstrapping is even less realistic for BIPOC women. One in four black women are impoverished. A quarter of latinx women are also impoverished. Indigenous women in the U.S. fair even worse; they are the most impoverished group with 28% living in poverty. For white women, the figure is roughly one in 10.

Setting aside for a moment that the ever-increasing global economic inequality de facto increases the entry barriers to entrepreneurship for everyone not belonging to the 1% of wealth owners, women entrepreneurs are disadvantaged from the very outset – having to contend with the gender wage gap, earning 85 cents for every dollar that men earn, and the childrearing disparity, spending two to three times more hours than men on unpaid childcare and domestic work according to the World Bank. While the systemic reasons for these phenomena could warrant an entire doctoral dissertation, they are very real and prove to be genuine obstacles to entrepreneurial glory.

Despite all of that, let’s assume that you are able to get your startup off the ground. The next round of fundraising is typically “friends and family.†As the name implies, this entails raising anywhere from $10,000 to $150,000 from your closest loved ones. Friends and family rounds are, once again, an opportunity afforded to those who have a network of people with disposable income to put at risk. This is a massive obstacle for black entrepreneurs; incomes for black US households in 2018 were ~39% lower than non-Hispanic white households and ~24% lower for Latinx. This income gap is not meaningfully closing. Unfortunately, BIPOC entrepreneurs cannot turn to their wealthier white friends for capital as those white friends often do not exist. As explained in Robin DiAngelo’s book and peer-reviewed journal article of the same name, “White Fragility,†racial segregation is alive and well.

White-flight, red-lining, gentrification, and a host of other causes perpetuate racial segregation in the US, but this phenomenon is not limited to the US alone. The University of Toronto’s Richard Florida and concurrently the Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities project found that similar levels of economic and racial segregation exist across major european cities including, London, Amsterdam, Stockholm, Oslo, Vienna, Madrid, Milan, Athens, Budapest, Prague, Riga, Vilnius, and Tallinn.

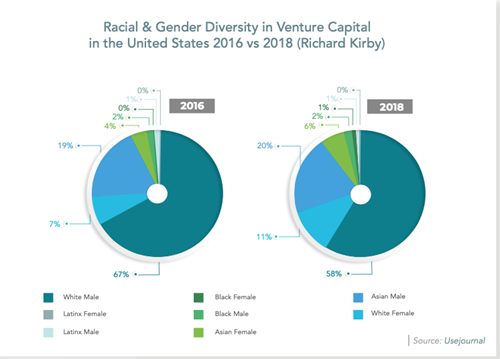

Assuming you are still successfully traversing the entrepreneurial “valley of death’ (the period of time when your costs are higher than your revenue), the next step in your fundraising process is raising capital from business angels and venture capital funds. With pitch deck in hand, you prepare to pitch your startup to a venture capital firm when you are met with your next barrier – an overwhelming sea of white faces. Venture capital firms are run by a 70% majority of white people: 58% are white men and 12% are white women. Women, in general, comprise only 18% of the industry and a mere 1% are black women.

Venture capitalist Richard Kerby cleverly argues that this creates a “mirror-tocracy,†one in which investors invest in others who look like themselves. If you are unconvinced of the mirror-tocracy,†consider the fact that 40% of the venture capital industry have been educated at two institutions alone: Harvard and Stanford. Do both of those institutions have world-class venture capital and entrepreneurship programs? Yes. Can their overwhelming dominance of the industry be solely credited to program quality alone? Absolutely not. Scores of other world-class educational institutions have comparably phenomenal programs. As Kirby puts it, “everyone wants to work with those they are most similar to, and education, gender, and race are attributes that allow people to find similarities in others.†This inclination of investors to fund individuals who are similar creates a vicious cycle where women and BIPOCs are systematically left out of the entrepreneurial process.

These structural inequalities are not only covertly reinforced but are also whole-heartedly accepted. Out of more than 100 investors that Morgan Stanley interviewed, 60% believed that women and minority groups obtained the right amount of funding while 20% of them argued that they received more than they deserved. Furthermore, 38% of male investors believe that women-led startups were not a priority, and 31% of white investors said that minority-led startups were also not a priority. Let’s remember that only 2% of venture capital funding currently goes to women and yet 60% of the industry believes that is the appropriate amount of funding and 20% believe that is too much.

At the risk of turning this into an essay on the intricacies of sociology, let’s briefly explore some of the underlying reasons for these disparities within entrepreneurship:

The gender roles that we have historically ascribed to women have been inherently limiting. Women are often told as children to be quiet, orderly and well-behaved, whereas we encourage boys to be boisterous (or at the very least tolerate it), competitive, and aggressive. It is these very traits that we encourage in boys that are very useful in entrepreneurship. As a result of being raised to fit the “girl†archetype, women tend to underestimate their own abilities, are more likely to ask for less in salary negotiations, are less prone to overconfidence, are more risk-averse, and are more likely to be disliked for having managerial aspirations (often and unfortunately being described as a “bitch†when acting on those aspirations); there is a litany of research to back this up. Women are also often discouraged and peer-pressured out of STEM fields and encouraged to pursue more traditionally female careers, which also tends to contribute to the wage gap–despite the fact that more women achieve higher educational levels than do men. Just look at the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Women’s 2017 report that found that less than 35% of women believe that they have the capabilities to start a business. This is not an aptitude problem, but a messaging one.

Similarly, we tell and retell limiting messages to BIPOCs. In a study exploring self-fulling prophecies (the notion that the stories we tell ourselves internally have a direct influence on real-world outcomes), black students did better in a mini-golf challenge when they were told golf is a test of athleticism; they did worse when told it was a test of intelligence. As much as we might hate to admit, we are, in some part, the people that society tells us we are. Our identities are self-affirmed in our experiences and externally affirmed in how we are treated. In many ways, this is cemented by the media we consume and the personalities we celebrate. It’s also no small wonder that women and BIPOCs have fewer public role models than do white men.

This is also true of entrepreneurs. Think of an entrepreneur right now. Do you have someone in mind? Is it Steve Jobs, Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, or Sergey Brin? The current zeitgeist celebrates white male entrepreneurs. If you thought of Cher Wang, Oprah Winfrey, Indra Nooyi or Sara Blakely, then you should be earnestly commended!

Let’s not mince words – the situation is bleak for female and BIPOC entrepreneurs. However, it has not gone unnoticed. There are some very promising funds that are seeking to rectify this huge imbalance. For example, Intel’s Capital Diversity Fund has committed $125 million to invest exclusively in ‘underrepresented tech entrepreneurs’ including women, minority groups and LGBTQ+. They helped back Brit&Co, a lifestyle website centered around DIY crafts for women, which raised a total of $42.6M across four rounds of funding since 2012. There is also Rethink Impact that exclusively invests in women; their $112 million fund invests in women-led, for-profit social enterprises. Merian Ventures’ $100M fund invests in female founders within the tech sector; Golden Seeds $100M fund invests exclusively in women; Backstage Capital and “It’s About Damn Time†$36M fund invests exclusively in black women.

This is certainly a welcome start to encouraging a diversity of voices in the innovation process but more is needed. Money managers and asset owners need to be much more thoughtful and aware of their implicit biases. Universities, incubators, and accelerators need to actively encourage women and BIPOCs to think of entrepreneurship as a real possibility. We need to raise empowered girls and feminist boys. We need to address race and access to economic opportunity, both from top-down policy (education reform, economic incentives, access to affordable childcare, etc.) and bottom-up action (hiring and recruiting practices, wage transparency, etc.). Of course, there is a lot to be done, but each of us acting within our zones of influence can meaningfully contribute to building a more diverse and equitable world.

Want to read more inspiring stories about women in leadership?

Download the Geneva Business School Magazine now.

The views expressed in this magazine are those of the authors or interviewees and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Geneva Business School or the editors of the magazine.